Solar flares are large explosions from the surface of the sun that emit intense bursts of electromagnetic radiation. The intensity of the explosion determines what classification the flare belongs to. The most powerful are X-class flares, followed by M-, C-, and B-class; A-class flares are the smallest.

These flares can be visible as bright flashes in a particular region of the sun and can last several minutes, according to the University Corporation for Atmospheric Research (UCAR).

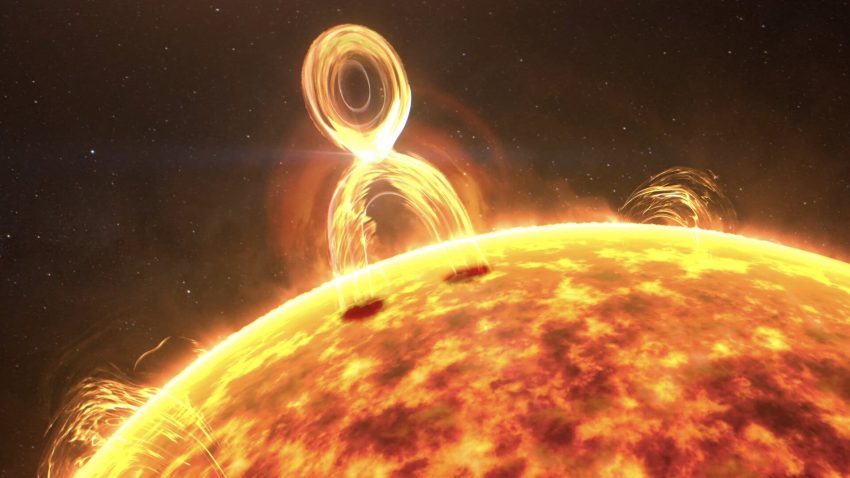

Solar flares occur when magnetic energy builds up in the solar atmosphere and is released suddenly. These outbursts are intrinsically linked to the solar cycle — an approximately 11-year cycle of solar activity driven by the sun’s magnetic field.

What Causes Solar Flares?

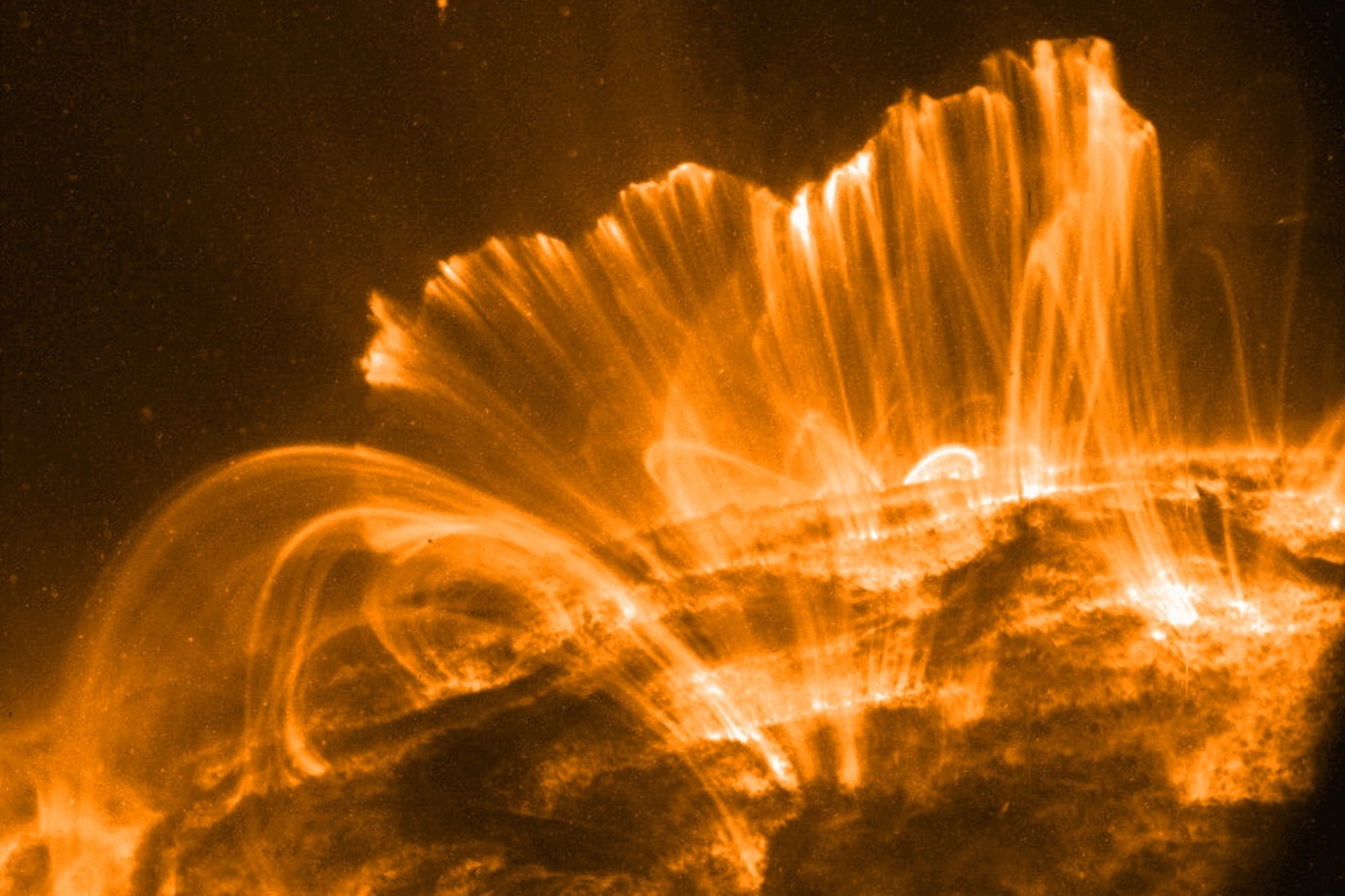

The sun’s surface is a magnetically mixed-up place. Magnetic fields are created from electrically charged gases generating electrical currents that act as a magnetic dynamo inside the sun, according to a statement from NASA. These magnetic fields twist, tangle, and reorganize themselves due to the turbulent nature of the gases that create them, according to NASA Space Place. This unsettled magnetic field behavior — also known as solar activity — can trigger solar flare eruptions from the surface that release vast amounts of electromagnetic radiation — a form of energy that includes radio waves, microwaves, X-rays, gamma rays, and visible light.

Solar flares tend to originate from regions of the solar surface that contain sunspots — darker, cooler portions of the solar surface where magnetic fields are particularly strong. As such, the number of sunspots can indicate the likelihood of a solar flare eruption.

Solar flares tend to originate from regions of the solar surface that contain sunspots. Solar activity follows an approximately 11-year cycle with the peak of sunspot activity coinciding with the solar maximum and a sunspot hiatus coinciding with the solar minimum, according to the Space Weather Prediction Center of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). During periods of low solar activity when no sunspots are present, it is unlikely that a solar flare will occur.

Solar activity is on the rise as we experience solar cycle 25. Solar maximum is predicted to occur in 2025.

Types of Solar Flares

There are five classes of solar flares, according to NOAA. Their designation depends on the intensity of X-rays emitted. Each class letter represents a 10-fold increase in energy output, similar to the Richter scale that measures the strength of earthquakes.

According to NASA, X-class flares are the most powerful solar flares. Then there are M-class flares that are 10 times smaller than X-class flares, then C-class, B-class, and finally A-class flares which are too weak to significantly affect Earth. Within each letter class, a finer scale from 1 to 9 gives the flare assessment greater precision with larger numbers representing more powerful flares within the class.

However, X-class flares can break this nine-point rating mold with higher ratings, since there is no class more powerful than X-class. According to NASA, a 2003 solar flare was so powerful it overloaded the sensors measuring it. The sensors reported an X28 flare before cutting out. Fortunately, X-class flares occur on average about 10 times per year, and flares as powerful as the one recorded in 2003 are even less likely.

How Do Solar Flares Affect The Earth?

Different types of flares, particularly X-class flares, affect Earth, satellites, and even astronauts.

Luckily for us, A and B-class solar flares are the most common and are also the weakest of the solar flare classes, too feeble to affect Earth in any significant way. C-flares are also fairly weak, exhibiting little or no effect on Earth.

With the two largest classes of flares, things start to get a little more interesting. Strong M-class and X-class flares and can trigger coronal mass ejections — a large release of plasma and magnetic field from the sun. This behavior can disrupt Earth’s magnetosphere and result in geomagnetic storms. Such geomagnetic storms can lead to auroras closer to the equator than is possible during calm conditions.

In 1989, a large solar flare accompanied a coronal mass ejection and hit Earth, plunging the entire province of Quebec, Canada, into an electrical blackout that lasted 12 hours, according to a NASA statement. The solar eruption triggered a geomagnetic storm on Earth, resulting in aurora borealis, or northern lights, that could be seen as far south as Florida and Cuba.

Solar radiation storms can also emit fast-moving charged particles, which carry a lot of energy and can endanger astronauts and Earth-orbiting spacecraft. During these storms, astronauts on the International Space Station need to seek shelter and all extravehicular activities are paused. Radiation-sensitive systems on satellites are powered down until the radiation storm has passed.

During an eruption, M-class and X-class flares can also cause minor to extensive radio blackouts on the side of Earth facing the sun. Radio blackouts mostly affect High Frequency (HF) (3-30 MHz) radio communications though sometimes Very High Frequency (VHF) (30-300 MHz) and higher frequencies can be affected.

Radio blackouts are caused by higher electron densities in the lower ionosphere of Earth’s atmosphere — the layer through which radio waves pass. The enhanced electron density causes radio waves to lose more energy as they travel through the layer, preventing them from reaching higher layers that refract the radio signals back down to Earth.

Solar Flare Predictions

The radiation emitted from solar flares travels at the speed of light and can reach Earth from the sun in just over 8 minutes. As such, we don’t have long to respond to such outbursts. Predicting space weather is tricky but our ability to do so has improved over the last few decades.

Powerful flares can significantly affect spacecraft, satellites, and ground-based technologies, and don’t give us a whole lot of notice before striking. Numerous organizations — including NASA, NOAA, and the U.S. Air Force Weather Agency (AFWA) — are keeping a watchful eye on the sun and monitoring it closely for powerful flares and associated magnetic storms. These organizations can send out warnings to technology sectors vulnerable to solar flare activity so that appropriate precautions can be taken.

In general, solar flares are nothing to worry about. So-called “killer flares” do not exist and although solar flares can significantly disrupt the technological world, they don’t contain enough energy to do any lasting damage to Earth itself.